“We are writing a new history for Colombia, Latin America and the world,” declared Gustavo Petro, the winner of Colombia’s presidential election, in Bogotá on June 19th. “Change”, he said, “will open opportunity and hope for all Colombians in every corner of the national territory.” The portentous tone was understandable. When he takes office on August 7th Mr Petro will become the country’s first left-wing president. He offers a radical departure from two decades of right-wing and centre-right rule. Mr Petro’s running-mate, Francia Márquez, a 40-year-old environmental activist, will become the country’s first black vice-president.

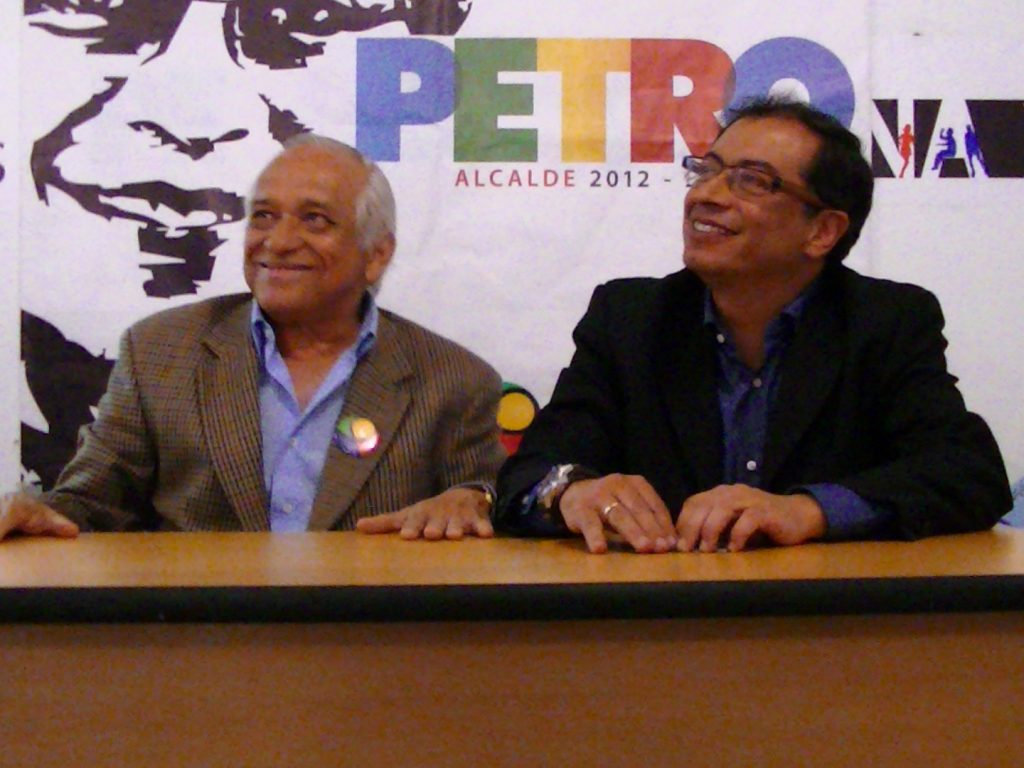

Mr Petro won by 50.4% to 47.3%, a wider than expected margin, in a run-off against Rodolfo Hernández, a property tycoon. His 11.3m votes, helped by a record turnout of 58%, mark the highest tally in Colombia’s electoral history. Mr Petro is a former mayor of Bogotá and once belonged to m19, a leftist guerrilla group. His win is part of a broader trend in Latin America in which leftists with iconoclastic agendas are winning elections. Mr Petro said his government would “develop capitalism, not because we adore it, but because we have to overcome premodernity and feudalism.”

His win was a victory for press-the-flesh campaigning over social-media savvy. With polls forecasting a tight race Mr Hernández, who reached the second round thanks mainly to finger-jabbing rants on TikTok, needed to mobilise conservative and centrist voters. But in the final week he cancelled media appearances and flew to Miami, saying his life was at risk. His standing among conservative types took a further hit when a video emerged of him dancing to reggaeton on a yacht in the presence of a dozen young women in bikinis.

Mr Petro cut a more statesmanlike figure. Having previously appeared behind bulletproof shields at big rallies, he spent the last week gamely chopping sugar-cane in the Andes, riding across Colombia’s eastern plains and picking coffee in the agricultural heartland. Mr Petro had run for the presidency twice before, leaving his movement, Pacto Histórico, well organised and effective at mobilising grassroots support.

Nevertheless, many Colombians remain deeply distrustful of their president-elect. Polls taken before the election found that he was less popular among older voters who lived through the 1980s and 1990s, a particularly violent period of the country’s long-running civil war. For many such voters Mr Petro’s membership of M19 is difficult to swallow. Others fear that his plans for increased social spending and curtailed oil exploration could sink an economy that has been one of the region’s most consistently strong performers. The IMF reckons Colombia will grow by 5.8% in 2022.

The coming days should provide clues to the new government’s direction. Pacto Histórico will hold only 15% of seats in the Senate and the Chamber of Representatives, so Mr Petro will have to seek alliances. He will also reveal pivotal members of his cabinet. “The tone will be set by his minister of finance,” says Juan Carlos Echeverry, a former finance minister and head of Ecopetrol, the state oil firm.

It is not clear what Mr Petro will do if he cannot build an effective coalition. He has a reputation for authoritarianism, derived in part from his time as mayor of Bogotá and his closeness—often exaggerated by his opponents—to the regime of Nicolás Maduro, the autocratic leader of Venezuela, a country with which Mr Petro plans to normalise ties. Many fear that Mr Petro’s plans to “democratise” Colombia’s institutions means stuffing them with his followers.

Mr Petro’s win is also part of a wider regional shift. Following the elections of left-wing candidates in Mexico, Peru and Chile, Latin America’s recent political swing has drawn comparison to the “pink tide” of the early 2000s, when left-leaning presidents dominated the region. But their recent success owes less to ideology than to strong anti-incumbent sentiment and a growing distrust of conventional politics. According to one poll 81% of Colombians see corruption as one of the country’s main problems, ahead of inequality (58%) and insecurity (57%). Only 5% have a favourable opinion of the country’s political parties. In 2019 and 2021 protests that racked the country were ferociously repressed by the police, apparently with the government’s approval. That left many younger people distrustful of the political establishment.

Many observers had feared that violence would also plague the election. But the vote was peaceful. Mr Hernández made a short concession speech shortly after the polls closed. Mr Petro struck a conciliatory tone at his victory rally, promising that his opponents would be welcome to discuss policy and that he would not bully his critics.

As night fell in Cali, a city badly affected by last year’s protests, the streets reverberated to the sound of cars honking in celebration. “Petro represents change,” said Paola Quiñonez, a human-rights activist who took part in the demonstrations. “If the economy suffers, that’s ok. The people have lived through hunger, poverty and insecurity before. The people will hold on.”

The Economist